I recently received this from John, who wrote :

“ Saw this and thought of you”.

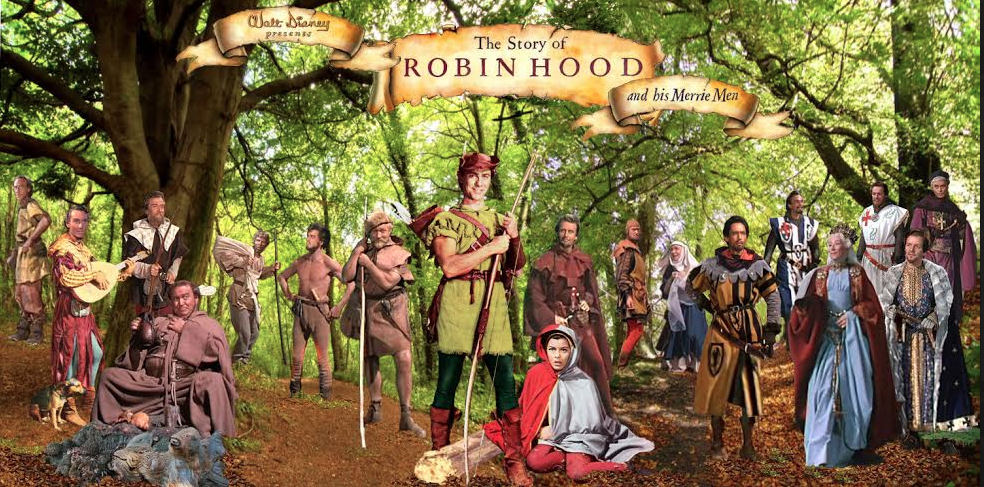

John sent me this signed picture of Ken Annakin (1914-2009), the legendary director of Walt Disney’s Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952). In 2009, shortly after his sad death, I reproduced his obituary from The New York Times:

"Starting as a cameraman in Britain on training films for the Royal Air Force in World War II, Mr. Annakin went on to direct more than 40 feature films for the British screen and Hollywood.

His 1965 comedy about the early days of aviation, the full title of which is Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew From London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes, starred Stuart Whitman as an American flier racing for a prize awarded by a British newspaper. It intertwined romance, cheating and international conflicts with soaring flight scenes. It earned Mr. Annakin an Oscar nomination, with Jack Davis for best screenplay.

Comedies were Mr. Annakin’s specialty in his early directing days. One hit from those years was Miranda (1948), with Glynis Johns as a mermaid caught by a doctor on a fishing trip; her tail reappears whenever she gets wet. In 1948 and ’49 Mr. Annakin directed a series of films about a down-to-earth British family, the Huggetts.

One of the first live-action Disney movies was Mr. Annakin’s “Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men,” with Richard Todd as Robin Hood. Shot in England and released in the United States in 1952, it entered many more childhood memories when it was shown on television in 1955. Another Disney film directed by Mr. Annakin was the 1960 version of “Swiss Family Robinson,” with John Mills, Dorothy McGuire and James MacArthur.

|

| Ken Annakin with Claudette Colbert at the premiere of Robin Hood |

Some of Mr. Annakin’s work was more serious. In 1957 he directed “Across the Bridge,” in which Rod Steiger played a Wall Street swindler hiding in Mexico using the identity of a man he had murdered. Mr. Annakin’s daughter said “Across the Bridge” was her father’s favorite film.

In 1962 Mr. Annakin was one of the four directors of “The Longest Day,” the sprawling World War II epic about the invasion of Normandy. He directed the scenes involving British and French troops.

In 1965 he was the sole director of “Battle of the Bulge,” with Henry Fonda.

Among Mr. Annakin’s other directing credits are “The Biggest Bundle of Them All” (1968), a comedy heist movie set in Italy; “The Call of the Wild” (1972), starring Charlton Heston; and “The Pirate Movie” (1982), an adaptation of “The Pirates of Penzance” starring Kristy McNichol and Christopher Atkins.

Kenneth Cooper Annakin was born in Beverley, in Yorkshire, England, on Aug. 10, 1914. His daughter said he was an only child who left his parents as a teenager and never told her his parents’ names. Besides his daughter, he is survived by his wife of 49 years, the former Pauline Carter; two grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

After dropping out of school, Mr. Annakin traveled to Australia, New Zealand and the United States. He returned to England and sold insurance and cars, then joined the RAF.

In 2002 Queen Elizabeth named Mr. Annakin an officer of the Order of the British Empire.”

To read a lot more about Ken Annakin and his work for Walt Disney on The Story of Robin Hood, just click on the label here.

w~~_12.jpg)