|

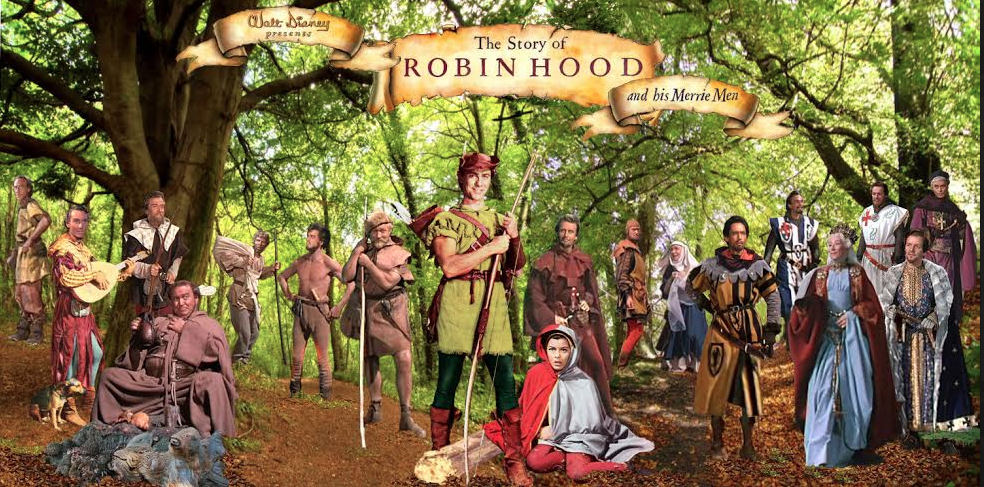

| Friar Tuck played by James Hayter |

So this time I have decided to attempt a recipe taken from a fifteenth century manuscript (Laud MS. 553 from about 1420). This was a dessert that Friar Tuck might have been familiar with. It was known as Pommesmoille:

Nym rys & bray hem in a morter; tempre hem up with almande milke, boile hem. Nym appelis & kerve hem as small as douste; cast hem in after the boillyng, & sugur; colour hit with safron, cast therto goud poudre, & zif hit forth.1 lb cooking apples, peeled, cored and finely diced.

2-4 oz ground almonds

2 cups water, milk or a combination.

1/2 cup of sugar (less if apples are sweet)

1/4 cup of rice flour

1/2 tsp of cinnamon

1/8 tsp of ginger

A pinch of ground cloves, salt, nutmeg

optional: pinch of saffron.

Mix sugar, rice flour and almond milk* in a saucepan; stir in sliced apples and bring to a boil over medium heat.

|

| The chopped apple |

|

| The mixture before adding the apples. |

Combine a spoonful of the pudding and all seasonings except nutmeg in a small dish or cup, then stir mixture into the pot of pudding. When thoroughly blended, pour into a serving dish. Sprinkle nutmeg on top and allow to cool. This dish may be eaten either hot or cold.

|

| Pomesmoille |

Jules and I tried the Pomesmoille warm and thoroughly enjoyed it. It was fascinating to think that we were tasting something that was eaten during the reign of Henry V and at the time of the Hundred Years War. It tasted rather like a spicy apple pie, but without the pastry. Next time I want to try it with cream!

*Almond milk was a regular ingredient in medieval dishes. It is obtained by steeping ground almonds in hot water or other hot liquid, then straining out the almonds, so that the milk is thick and smooth, not gritty. The milk was either wrung through a clean cloth or forced through a fine strainer and the more almonds you use in proportion to water, the smoother, tastier and creamier the almond milk will be. For quickness I cheated and bought mine from a supermarket!